Establishing the Comerton Home

Soon after Thomas Hodge arrived in Newport in June 18911 as the new pastor of the Congregational Church he determined to wake the people of Newport up to their responsibilities to the disadvantaged members of society. He was a popular, young (well, 31), Welsh, recent graduate of Oxford2 who wasn’t afraid to speak his mind. He could fill the church with his sermons (although a talk about the Salvation Army’s work in Dundee was rather less well attended).3 By October that year, he had proposed, from the pulpit, a convalescent home in Newport for poor children from Dundee. The home should be run by the people of Newport on a voluntary basis, similar to the facility already in operation for adults [this is a reference to Mrs Berry’s house for invalids at Den Cottages].4 He was sure money and assistance would be forthcoming and pledged £20 himself to the fund.

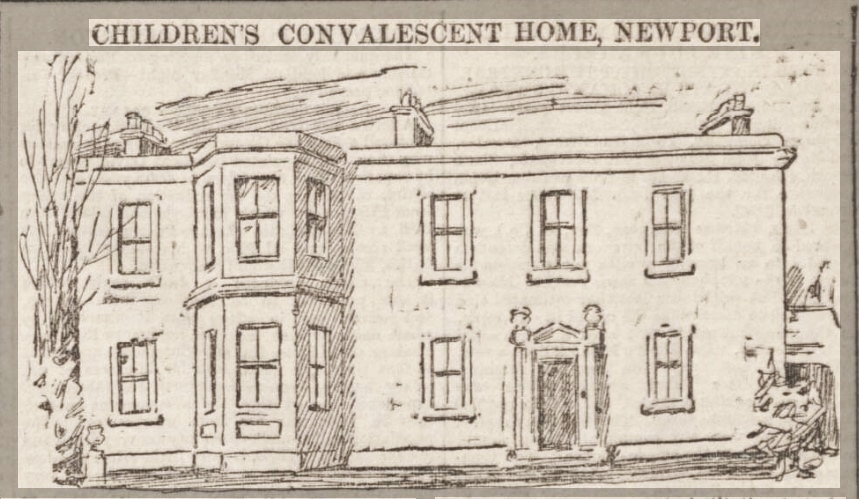

By December that year, considerable support had been gained. The difficult search for a suitable property had eventually resulted in Woodbine House (now 11-11a King Street) being purchased for £740. It was a commodious building with a large secluded garden. Whoever spoke to the Courier, I suspect it was Hodge himself, considered it ‘in every respect well adapted for the purpose’. The object of the Home would be to provide a change of air and scene free of expense to poor children belonging to Dundee and neighbourhood during the period of their convalescence after illness. It was proposed to admit girls of from 4 to 14 years of age, and boys from 4 to 10 or 12, and to board each of them for a fortnight or a month. The idea was to begin in a small way – maybe 10 or 12 children at a time – so around 300 would enjoy the advantage of a change of air with bright and happy surroundings over a year. A committee was to be set up, without regard to sect, to administer the scheme. The home itself would be under the charge of a properly qualified matron who would reside in the institution, assisted by voluntary workers. Dr Stewart had volunteered to act as medical officer – every child would be examined before admission to prevent infectious diseases being introduced. The newspaper was sure the scheme would meet with hearty support from the generous citizens of Newport and Dundee.5

It turns out that Woodbine House, which had previously been unsuccesfully marketed at a price of £1000, had been bought by a group of several Newport gentlemen for the purposes of setting up a children’s convalescent home – before the public meeting at which the home would be officially set up.6

On 14 January 1892 a public meeting agreed to the proposals and a committee was elected. Expenses were to be defrayed by public subscription and gifts in kind. Estimated costs: £740 for purchase of the house, £250 for alterations and furnishings; with 12 children the running costs would be £200 – £300 per year. A gentleman had offered to pay the rent or equivalent for 5 years and there were many other expressions of support.7

Well, you can lead a horse to water …

There must have been many heated discussions in Newport in early 1892.

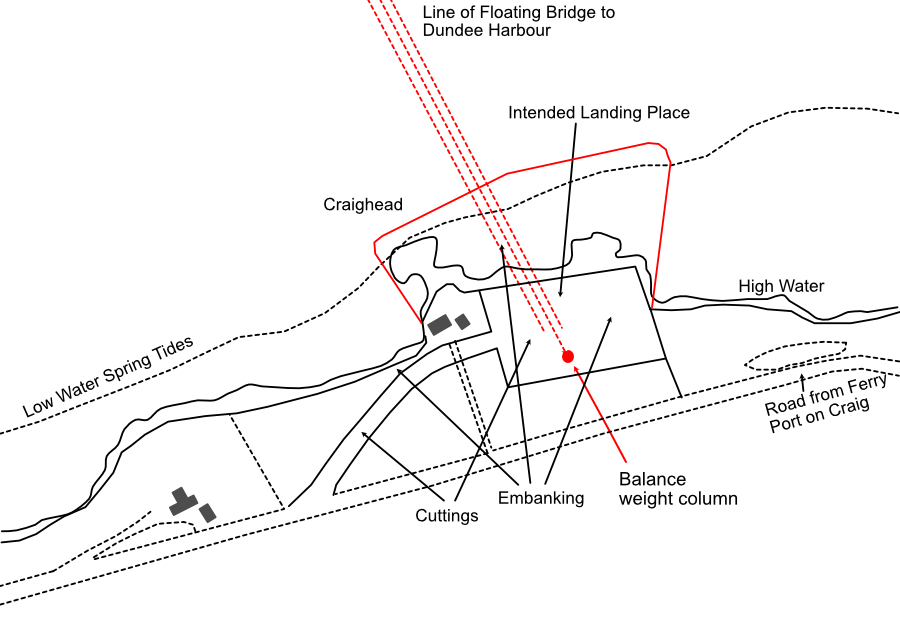

By February, the management committee had decided that Woodbine House which had previously been ‘well adapted for the purpose’ was now ‘somewhat unsuitable for such an institution’ – it would ‘need extensive alterations’ and ‘it would be expedient for sanitary reasons to have the Home situated outside the burgh boundaries’. (Bear in mind that Newport had excellent piped water and gas supplies, and mains drainage, whereas a location outside the burgh boundaries would have none of them.) So the committee ultimately agreed to back down on the use of Woodbine House and to have a new building erected, outside the burgh. The location was undecided but an architect would draw up the plans free of charge and St Fort would provide the ground if required.8

So what of Woodbine House? At that same meeting it was decided to transfer the property to Mr D S Smith who had offered to purchase it if the committee had decided on building afresh.

By April, St Fort had arranged for a site for the erection of a new building and plans had been prepared. A delay was required, however, to allow for an application for more funding from the Cobb bequest.9 This delayed the project somewhat. (David Cobb left £60000 for charitable purposes. His trustees were, of course, inundated with requests.) The Evening Telegraph called for action on the home.10

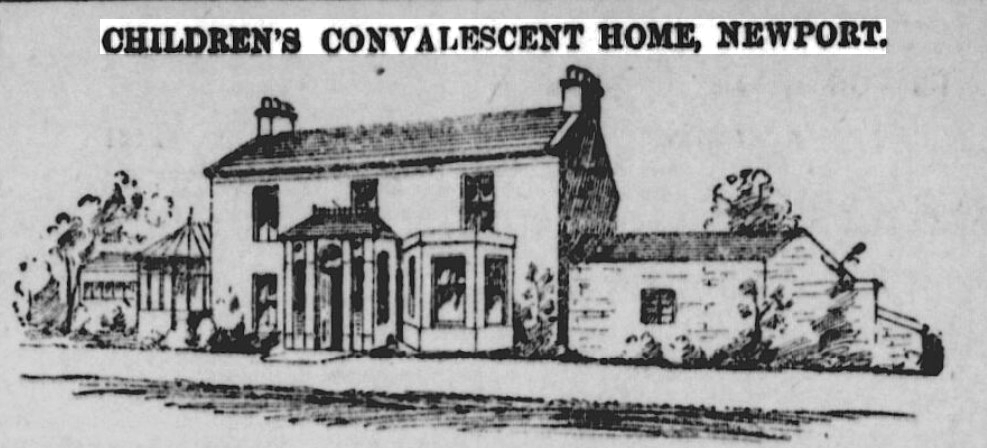

Eventually, progress was made. Having apparently given up waiting for the Cobb Trustees, in January 1893 Comerton House, the property of Mr Arthur Smith, was first leased, then purchased.11

Comerton is described as being very suitable. Miss Stead has been employed as Matron.12, 13 (Comerton, at that time surrounded by open fields but now opposite the entrance to Drumoig, is not only outside the burgh boundary, it is also outside the parish boundary!)

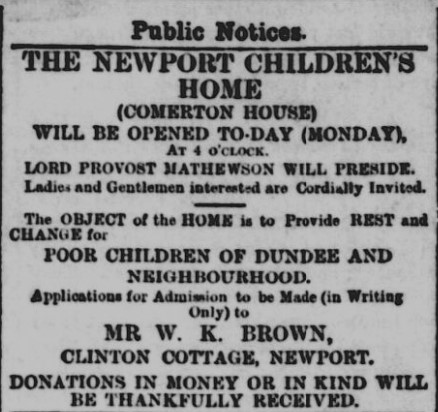

The home opened at Comerton on 12 Jun 1893.14

Rev. Hodge continued as president of the management committee until 1900 when he left his Congregational charge in Newport and moved to Leicester. By then, 1220 children had passed through the home’s doors, the building had been extended and a good water supply had been added.15 (well, well!)

The Comerton Home went on very successfully for many years. The original management committee eventually offered the premises for sale in 1956.16

The Constitution of the Management Committee is here and there is an article about the home on the Children’s Homes website.

Sources:

- Dundee Courier, 27 Jun 1891, p5 (all newspapers available at British Newspaper Archive)

- Oxford Men 1880-1892, Joseph Foster, 1893 (at the Internet Archive)

- Dundee Evening Telegraph, 24 Aug 1891, p3 and 15 Oct 1891, p3

- Dundee Courier, 19 Oct 1891, p3

- Dundee Courier,25 December 1891, p4

- Dundee Courier,13 Jan 1892, p3, plus sketch

- Dundee Advertiser, 15 Jan 1892, p7

- Dundee Evening Telegraph, 17 Feb 1892, p3

- Dundee Courier, 22 Apr 1892, p3

- Dundee Evening Telegraph, 8 Oct 1892, p3

- Fifeshire Journal, 19 Jan 1893, p6

- Dundee Advertiser, 28 Jan 1893, p3

- Dundee Courier, 13 May 1893, p6, plus sketch

- Dundee Courier, 12 & 13 Jun 1893

- Dundee Evening Telegraph, 28 Mar 1900, p5

- Dundee Courier, 31 Dec 1955, p1